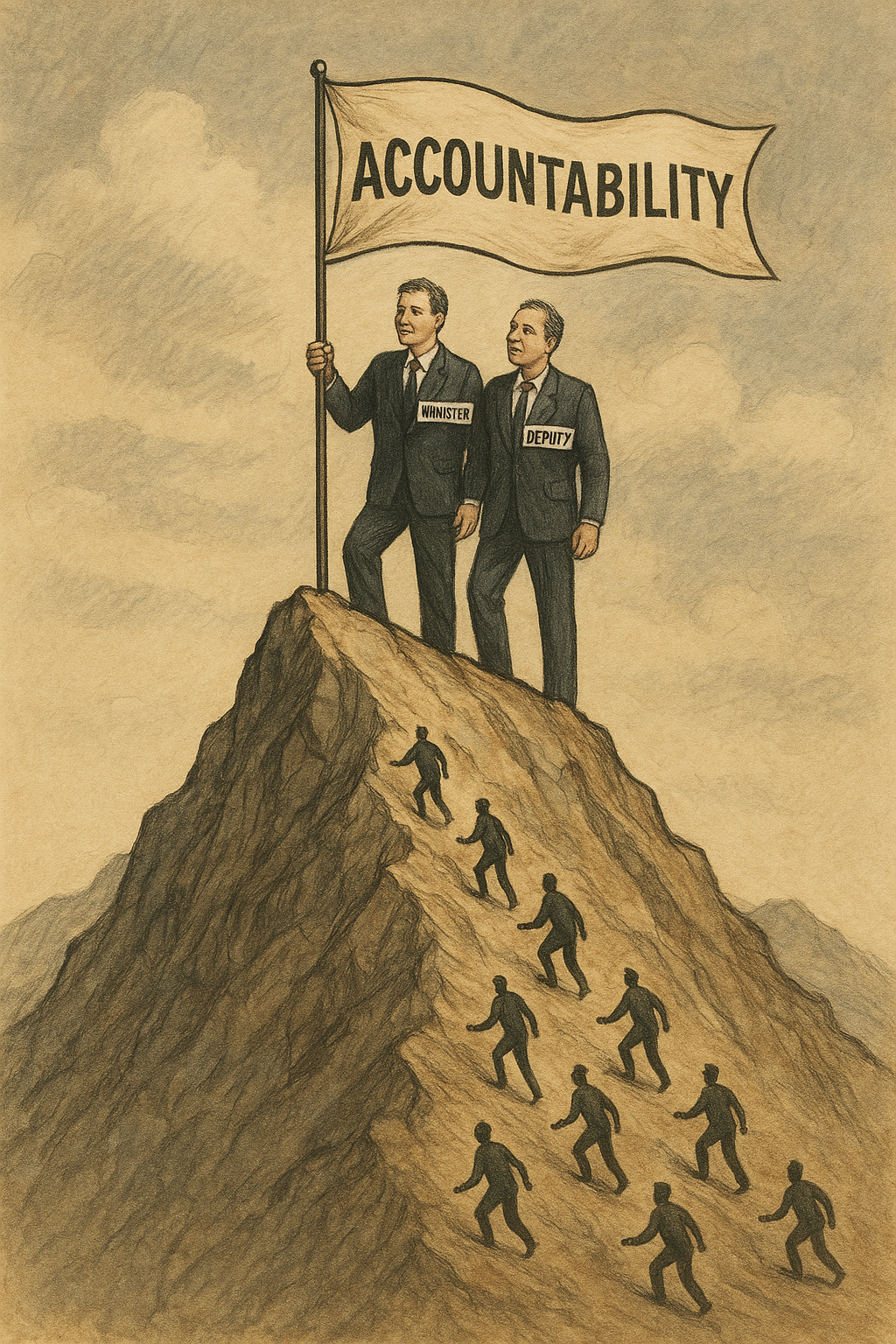

At the Peak of the Pyramid

Ministers and Deputy Ministers stand at the summit of Canada’s public service and political governance structure. While the operational machinery of government depends on Directors General and Assistant Deputy Ministers, the tone, pace, and cultural priorities of the system are ultimately set at the very top.

In the Westminster model, the Minister bears political accountability while the Deputy Minister holds stewardship of the public service. Together, you embody both the democratic legitimacy of elected office and the professional continuity of a non-partisan bureaucracy. This dual accountability makes your role uniquely powerful—and uniquely exposed.

The question is not simply what decisions you make, but how you lead through decision-making itself. For transformation to succeed, Ministers and Deputies must model accountability as a cultural practice, not just a compliance exercise.

The Symbolic Power of the Summit

Every choice made by Ministers and Deputies resonates far beyond the immediate issue at hand. Signing off on a Treasury Board submission or approving a regulatory change is not just a technical step—it sends a cultural signal about speed, ownership, and trust.

Political scientists note that “tone from the top” is one of the most decisive factors in shaping bureaucratic culture (Savoie, 1999; Aucoin, 2012). When Ministers and Deputies demonstrate confidence in their teams and own responsibility for decisions, this cascades downward. Conversely, when caution translates into chronic delay, the signal is equally clear: accountability is to be avoided, not embraced.

Decision-Making as Culture-Building

In risk-averse systems, decisions are often delayed in the name of prudence. Briefing decks circulate endlessly. Consultations expand until momentum collapses. Files climb the hierarchy with ever more caveats attached.

From the summit, Ministers and Deputies can either reinforce or disrupt this pattern. By closing decisions promptly, even when imperfect, you model a culture where progress matters as much as process. This aligns with insights from organizational behaviour: cultures evolve not through mission statements but through repeated behaviours that signal “the way things are done here” (Schein, 2017).

The Accountability Paradox

The Canadian public service is built on a paradox: while accountability is its defining principle, fear of accountability often paralyzes action. Public servants fear blame from central agencies, auditors, media, and Parliament. The result is what Donald Savoie has called “court government,” where decisions are hoarded at the top while the system underneath learns to defer (Savoie, 2008).

Ministers and Deputies must confront this paradox directly. If you treat accountability solely as risk containment, the system will mirror that defensiveness. If, however, you model accountability as ownership—a willingness to make choices, accept outcomes, and learn from them—you reset the cultural signal.

Ministers and Deputies as Cultural Catalysts

At your level, leadership is less about direct management and more about cultural catalysis. You rarely draft the policies yourself or design the programs. Your influence lies in:

- What you prioritize. Teams quickly notice which files you champion and which languish.

- What you tolerate. Delay and indecision become normalized if unchallenged.

- What you model. Courage or hesitation filters downward.

In this sense, every public interaction, every internal approval, and every Cabinet submission becomes symbolic. Ministers and Deputies cannot control every detail of government, but you can profoundly shape the culture in which details are handled.

Independent Insight: Seeing Beyond the Bubble

At the summit, isolation is a real risk. Ministers are surrounded by political staff who filter information for political risk. Deputies receive carefully curated analysis from ADMs and DGs who may understate problems to avoid blame.

This filter bubble can blind senior leaders to cultural realities on the ground. Independent insight from trusted advisors, peer networks, or external partners helps pierce that bubble. It provides perspective on how accountability is actually functioning throughout the system, not just how it appears in briefing notes.

For example, external assessments often reveal patterns such as:

- Files consistently delayed in middle management due to decision avoidance.

- Overreliance on process as a substitute for outcomes.

- Fear-driven cultures where innovation is quietly discouraged.

For Ministers and Deputies, such insights are invaluable. They allow you to act not only as decision-maker but as culture reformer.

Accountability in Action: Owning the Political-Administrative Interface

Ministers and Deputies also face the unique challenge of the political-administrative interface. Ministers answer to Parliament and voters; Deputies answer to the Clerk and the system of public service values. When aligned, this partnership is powerful. When fractured, accountability collapses into finger-pointing.

Owning this partnership is itself a cultural act. When Ministers and Deputies own decisions together and present a united front, they model shared accountability. Staff below take their cue accordingly. Research on governance confirms that “joint ownership of outcomes at the top reduces defensive behaviour throughout the hierarchy” (Lodge & Gill, 2011).

Courage as Cultural Leadership

For Ministers and Deputies, courage is not only political but cultural. Saying “yes” to a bold reform, closing a contentious file, or defending your officials against unfair criticism are acts that resonate throughout the system.

Courage at the summit legitimizes courage further down. When officials see that their leaders will back them if they take ownership, they take risks more confidently. The inverse is also true: when leaders deflect blame, everyone retreats into self-protection.

Conclusion: Leading Beyond Compliance

Ministers and Deputies are more than stewards of compliance. You are cultural leaders whose actions define how accountability is lived across the system. Every time you close a decision, defend your team, or signal ownership, you strengthen a culture of responsibility. Every time you defer endlessly or deflect blame, you weaken it.

Transformation in government depends on this cultural leadership. Systems modernize only when leaders at the summit demonstrate that accountability is not a threat but a practice of ownership. By modeling courage and decisiveness, Ministers and Deputies enable the entire public service to move beyond hesitation and toward meaningful change.

What’s Next?

At Institute X, we help senior leaders step beyond the risk-averse culture that holds transformation back. By providing independent insight and cultural analysis, we support Ministers and Deputies in modelling accountability, courage, and decisive leadership.

References

- Aucoin, P. (2012). Democratizing the Constitution: Reforming Responsible Government. Emond Montgomery.

- Lodge, M., & Gill, D. (2011). “Toward a New Era of Administrative Reform? The Myth of Post-NPM in New Zealand.” Governance, 24(1), 141–166.

- Savoie, D. J. (1999). Governing from the Centre: The Concentration of Power in Canadian Politics. University of Toronto Press.

- Savoie, D. J. (2008). Court Government and the Collapse of Accountability in Canada and the United Kingdom. University of Toronto Press.

- Schein, E. H. (2017). Organizational Culture and Leadership (5th ed.). Wiley.